Poetry did not exist for me before I discovered the work of Ted Hughes. Poetry did not exist for me before I discovered the work of Ted Hughes.

Then again perhaps it would be more accurate to say that it was the work of Ted Hughes that discovered me.

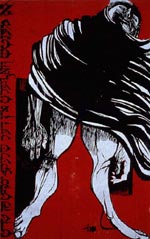

The time is late October 1998; the place is Cardiff, Wales. Jacob's antique market to be exact and I’m browsing its top floor book shop now long defunct. (All the bookshops I have loved are no longer standing). For reasons I don't remember, I bought a beautiful hardback edition of 'Crow', powerful cover art by Leonard Baskin included. (His scratchy yet solid depiction of ‘Crow’ seemed to buzz and boil with anguish and indignation; Crow seemed to be shouting ‘What the fuck is I doing trapped on this book cover! Get me the hell out!' And there was no doubt that this was a male of the species - Baskin has even added an angry pair of pert balls to Mr Crow). The time is late October 1998; the place is Cardiff, Wales. Jacob's antique market to be exact and I’m browsing its top floor book shop now long defunct. (All the bookshops I have loved are no longer standing). For reasons I don't remember, I bought a beautiful hardback edition of 'Crow', powerful cover art by Leonard Baskin included. (His scratchy yet solid depiction of ‘Crow’ seemed to buzz and boil with anguish and indignation; Crow seemed to be shouting ‘What the fuck is I doing trapped on this book cover! Get me the hell out!' And there was no doubt that this was a male of the species - Baskin has even added an angry pair of pert balls to Mr Crow).

As I say, I've no idea why I bought this book then. Although a voracious buyer of books, I was certainly not in the habit of buying poetry. School had killed any potential interest in this particular art form. Even the very word 'poetry' seemed inclined to lean in on itself with a heavy and portentous density. Some part of me still associated poetry with the wasted, baking afternoons trapped within the long ago classrooms of early summer. Outside the world is bright and green, a fiesta of frantic sexual motion and kinetic energy while in here all is musty, stifled and gagged. An all boy’s school rank in the broiling heat of early June is not the time and place to study the war poetry of Wilfred Owen. The agony is upped when one is instructed by teacher as to exactly what the words are meant to mean and precisely how one should feel upon reading them. As I say, I've no idea why I bought this book then. Although a voracious buyer of books, I was certainly not in the habit of buying poetry. School had killed any potential interest in this particular art form. Even the very word 'poetry' seemed inclined to lean in on itself with a heavy and portentous density. Some part of me still associated poetry with the wasted, baking afternoons trapped within the long ago classrooms of early summer. Outside the world is bright and green, a fiesta of frantic sexual motion and kinetic energy while in here all is musty, stifled and gagged. An all boy’s school rank in the broiling heat of early June is not the time and place to study the war poetry of Wilfred Owen. The agony is upped when one is instructed by teacher as to exactly what the words are meant to mean and precisely how one should feel upon reading them.

Yet years later and on my own terms (by now no one had forced me to read poetry for over a decade) ‘Crow’ flew straight into my hands eyes and heart. Flicking through the pages at random, the third poem grabbed me. It was ‘Examination at the womb door ' that did it. Yet years later and on my own terms (by now no one had forced me to read poetry for over a decade) ‘Crow’ flew straight into my hands eyes and heart. Flicking through the pages at random, the third poem grabbed me. It was ‘Examination at the womb door ' that did it.

"Who is stronger than hope?

Death

Who is stronger then the will?

Death

Stronger than Love?

Death

Stronger than life?

Death

But who is stronger than death?

Me, evidently

‘Pass, crow'

These words blew some nameless chamber within me wide open. I closed the book and said 'Fuck' out loud. I reopened the book. The poem remained upon the page while inside me something had been eerily rearranged. Transfigured. These words blew some nameless chamber within me wide open. I closed the book and said 'Fuck' out loud. I reopened the book. The poem remained upon the page while inside me something had been eerily rearranged. Transfigured.

What was weird about reading 'Crow' for the first time was that it didn't seem like a one way process. As much as I was reading it, it felt like the words, the poems themselves, were simultaneously taking something vital from me. What was weird about reading 'Crow' for the first time was that it didn't seem like a one way process. As much as I was reading it, it felt like the words, the poems themselves, were simultaneously taking something vital from me.

If it’s true, as William Burroughs has claimed, that 'Language is a virus' then I was a willing host to this particular infection. (I have come to believe that the same is true of most things, cigarettes and alcohol especially. They sit on the table begging to be consumed by us so that they may ‘Live’).

I felt better for the reading of this dark flinty language. I couldn't put my finger on why. I wasn't elated by Hughes' poetry as I was with some music and I was certainly not becalmed by it as with some literature. Yet something about these ugly beautiful poems - and they struck me a primitive and authentic as if transcribed from etchings on some prehistoric cave wall - there was something about them that made me feel affirmed, put on course, empowered and in tune.

Now that I was hooked I began to not only investigate Hughes' huge body of work further but I began to appreciate other poetry too – in particular Larkin, Carver, Yevtushenko, and Montale. Clearly some inner block, some emotional log jam had been cleared within me - blown away, in fact, violently and unequivocally. Now that I was hooked I began to not only investigate Hughes' huge body of work further but I began to appreciate other poetry too – in particular Larkin, Carver, Yevtushenko, and Montale. Clearly some inner block, some emotional log jam had been cleared within me - blown away, in fact, violently and unequivocally.

I began to buy anything with Hughes' name on it, and there was a lot to be bought. The Hughes Bibliography is a bibliophile’s wet dream. (And in this regard Keith Sagar and Stephen Tabor's exhaustive Bibliography of Hughes is a kind of pornography). Faced with such an impossible breadth of choice and my own limited resources, I quickly narrowed my criteria to collecting the most beautiful edition I could find and afford at the time. The very aesthetic voluptuousness of the books was aided and abetted by the fact that Hughes himself had found the perfect collaborator and visual foil in the visual art of Leonard Baskin. (In some ways an equivalent of the Hunter Thompson/Ralph Steadman relationship). Their partnership resulted in some ravishing offspring. (In Particular the Viking editions of 'Season songs', 'Cave birds' and 'Moon bells'. 'Capriccio'' remains the Holy Grail. A limited edition rarer than the crocodile tears of a Dodo).

I caught Hughes' final classic a year after it came out. 'Birthday letters' amongst other things was a eulogy for the almost mythical union between him and Sylvia Plath. The details of which, while exciting others rabidly, for some reason left me cold. (Simply put, I guess I've never particularly been excited by the sex and/or emotional life of those outside my own personal juridistriction). The Hughes obsessed Sunday Times seemed to consider the pair as a contemporary version of Orpheus and Eurydice and it was probably only this classical connection that raised the tone of the almost endless articles on the two to that above mere tabloid soap opera. I caught Hughes' final classic a year after it came out. 'Birthday letters' amongst other things was a eulogy for the almost mythical union between him and Sylvia Plath. The details of which, while exciting others rabidly, for some reason left me cold. (Simply put, I guess I've never particularly been excited by the sex and/or emotional life of those outside my own personal juridistriction). The Hughes obsessed Sunday Times seemed to consider the pair as a contemporary version of Orpheus and Eurydice and it was probably only this classical connection that raised the tone of the almost endless articles on the two to that above mere tabloid soap opera.

Ted Hughes – The So called patron saint of adultery, the feminist's Bette Noir, passionate hunter and fisherman, ladies’ man, Royalist and close friend of Prince Charles – this caricature was barely out of the broadsheets between '98 and 99. These posthemous appearances in the Sunday supplements were for many the only point of contact with Hughes. His actual raison d’être - the Poetry - seemed almost incidental in this context. Ted Hughes – The So called patron saint of adultery, the feminist's Bette Noir, passionate hunter and fisherman, ladies’ man, Royalist and close friend of Prince Charles – this caricature was barely out of the broadsheets between '98 and 99. These posthemous appearances in the Sunday supplements were for many the only point of contact with Hughes. His actual raison d’être - the Poetry - seemed almost incidental in this context.

Revealingly, friends who had received complimentary copies of 'Crow' from me remained either un interested or overly disturbed. 'I've put it in a box in the basement' one told me. 'And I shall open it when I'm fifty'. Revealingly, friends who had received complimentary copies of 'Crow' from me remained either un interested or overly disturbed. 'I've put it in a box in the basement' one told me. 'And I shall open it when I'm fifty'.

Discovering Hughes now marked another personal habit; that of getting into people soon after they died. As with pop music, I would always discover a band to find that they had broken up the Christmas before. Discovering Hughes now marked another personal habit; that of getting into people soon after they died. As with pop music, I would always discover a band to find that they had broken up the Christmas before.

As with the perfect pop group 'Japan', I would never get to see Hughes live. (He was, apparently an incredible presence when reading his work before an audience).

In 2000 I was recording an album, my sixth by then. As a matter of routine en route to the Harlesden studio via tube and train, I would listen to tapes of Hughes reading his poetry. One track I was then working on ('Just so you know') was built around an undulating drone, a heavy flat orchestral loop that suggested the slow motion shimmy of the earth's crust or the great nervy plates that make up Californian fault line. In 2000 I was recording an album, my sixth by then. As a matter of routine en route to the Harlesden studio via tube and train, I would listen to tapes of Hughes reading his poetry. One track I was then working on ('Just so you know') was built around an undulating drone, a heavy flat orchestral loop that suggested the slow motion shimmy of the earth's crust or the great nervy plates that make up Californian fault line.

On this particular track I wanted Hughes himself to introduce the song. I wanted to sample him and lay his heavy gravity voice over the opening bars. I spooled through the tape. Completely at random, without knowing the title, I chose the poet reciting the following lines:

‘And this is neither a bad variant nor a try out ‘And this is neither a bad variant nor a try out

This is where all the staring angels go through.

This is where all the stars bow down.’

Beneath the dense currency of Hughes' rich vocal timbre, the music swelled and inverted upon itself ceaselessly. Beneath the dense currency of Hughes' rich vocal timbre, the music swelled and inverted upon itself ceaselessly.

The words and the way they were spoken seemed to fit perfectly and while I knew I would never get clearance on either the use of Hughes’s portentous voice or his material, it was enough for now. It would inspire the rest of the track from therein and would be taken off at a later date.

It was only later when I identified the poem as 'Pibroch' that I realised the stunning co -incidence. The word

'Pibroch' meant ‘a kind of traditional Bag Pipe music' and 'variations on a dirge'. This was, uncannily a completely accurate description of the music.

(I mentioned this electric coincidence to prominent Hughes critic 'Keith Sagar; who I had by now fostered a friendly e-mail relationship with. Frustratingly his response was no response, his reply offering only to sell me some rare books).

As I continue to work my way through Hughes' oeuvre I continued to discover and was impressed by the sheer breadth of his range. A musical comparison would have been with 'Prince' at his mid eighties peak. As I continue to work my way through Hughes' oeuvre I continued to discover and was impressed by the sheer breadth of his range. A musical comparison would have been with 'Prince' at his mid eighties peak.

Both could inhabit varying genres with conviction yet without ever losing their original voice.

The very work that had been my introduction had also shaped one of the poets clichéd images ; it was because of 'Crow' that many saw Hughes as merely the King 'Goth' of English poetry. Yet as I began to discover, his work also embodied tenderness, whimsy and even humour. There was the delightful playfulness of probably his truest Children's book, 'Meet my Folks’ contrasting cosmically with poems about watching two spiders fucking through a magnifying glass. The very work that had been my introduction had also shaped one of the poets clichéd images ; it was because of 'Crow' that many saw Hughes as merely the King 'Goth' of English poetry. Yet as I began to discover, his work also embodied tenderness, whimsy and even humour. There was the delightful playfulness of probably his truest Children's book, 'Meet my Folks’ contrasting cosmically with poems about watching two spiders fucking through a magnifying glass.

Although much of his 'Children's poetry' was perhaps a tad to dark for the average five year old, it existed in itself and apart from the major works. The poems making up 'Moon Bells' and 'How the whale became' stood up on their own weird hooves, a kind of x - rated 'Jackanory'.

Yet again there was 'Moortown' his diary of life as a cattle farmer. By the time I discovered this book, I myself was living in the country and because of owning a horse, visited a farm twice daily. I was astounded at the realisation that the reading of 'March morning unlike others', from the warmth of my study made me feel as if I were standing in a field much more than actually standing in a field did. Yet again there was 'Moortown' his diary of life as a cattle farmer. By the time I discovered this book, I myself was living in the country and because of owning a horse, visited a farm twice daily. I was astounded at the realisation that the reading of 'March morning unlike others', from the warmth of my study made me feel as if I were standing in a field much more than actually standing in a field did.

This led me to another paradox - how could a Hughes Poem, like 'Crow's song of himself' seem to occupy the same emotional space as a novel? This led me to another paradox - how could a Hughes Poem, like 'Crow's song of himself' seem to occupy the same emotional space as a novel?

It occurred to me that some poetry at its best worked like a depth- charge - a kind of incredibly compressed force that exploded in the depths...the equivalent of the effect of a large tequila slammer compared to 6 slow beers, or death by a dum dum bullet compared to bleeding to death from a shoulder wound.

A year on from 'Pibroch' writing the words for the title track of the final Jack Album 'The end of the way its always been', I made a nominal effort to harness some of what Hughes called the 'Super ugly language' of Crow. I tried to apply the same kind of armoury to the subject matter - my immediate environment. I was at this point living in the very first year of the twenty first centaury a citizen of, as I saw them, the sub apocalyptic streets of East London's Dalston. A year on from 'Pibroch' writing the words for the title track of the final Jack Album 'The end of the way its always been', I made a nominal effort to harness some of what Hughes called the 'Super ugly language' of Crow. I tried to apply the same kind of armoury to the subject matter - my immediate environment. I was at this point living in the very first year of the twenty first centaury a citizen of, as I saw them, the sub apocalyptic streets of East London's Dalston.

‘Bad dreams are Bass in Shallow water ‘Bad dreams are Bass in Shallow water

Swimming underground

Asleep against the morning’

The inspiration of language behind these lines and the rest of the song was pure Hughes. The inspiration of language behind these lines and the rest of the song was pure Hughes.

It didn't matter if anyone picked up on this or not, this was not the point. It was his tone that influenced me here, a tone of language unknown to me before 'Crow'. Kind of like a minor trumpet player hearing Miles Davis for the first time.

But if this example of Hughes inspiring my own work is the most explicit I can quote its perhaps the most superficial too. Because if my own work relates to my true self at all, then it’s a self irrevocably moved and enhanced by the poetry of Ted Hughes. But if this example of Hughes inspiring my own work is the most explicit I can quote its perhaps the most superficial too. Because if my own work relates to my true self at all, then it’s a self irrevocably moved and enhanced by the poetry of Ted Hughes.

I took a profound step along the trail of my own personal evolution when in the last years of the twentieth centaury as a boy in my late twenties, for reasons that remain a mystery to me now; I bought a second hand copy of 'Crow' from a second hand bookshop in Wales. I took a profound step along the trail of my own personal evolution when in the last years of the twentieth centaury as a boy in my late twenties, for reasons that remain a mystery to me now; I bought a second hand copy of 'Crow' from a second hand bookshop in Wales.

|